The Tour de France Hall of Fame features many names that have been building the legend of the carrera for more than a century, but among them, the five-time champions stand out. Two Frenchmen; Jacques Anquetil and Bernard Hinault; one Belgian, Eddy Merckx; and one Spaniard, Miguel Induráin, have equally shared twenty victories in Paris. Once Lance Armstrong and his seven consecutive wins were removed from the list due to doping, the debate about who has been the best rider in the history of the Tour regained some consensus around Eddy Merckx, due to the overwhelming nature of his victories, his record number of stage wins and his dominance in the secondary classifications, or his amazing achievements outside France. But there are more nuances worth knowing that foster other kinds of opinions: circumstances, the quality of rivals, historical context, external factors... The best thing is to dive into the Olympus of the four five-time champions and learn what paths they followed to enter the legend. Learning about their four stories, with their feats, their records, their rivals, and the how and why of the end of their reigns, is to enter a kind of Olympus of the gods of road cycling, which inevitably merges with the very legend of the Tour de France.

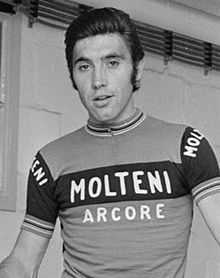

Eddy Merckx

The prodigious Belgian champion is considered the greatest cyclist in the history of the sport and also of the Tour de France, where he boasts an almost unbeatable record: five overall victories in Paris in just seven appearances, with 34 stage wins and 96 days wearing the yellow jersey. No one in more than a century of history has come close to such a combination of records, just as no one has approached his 525 victories, including five Giros d'Italia, one Vuelta a España, three World Championships, the Hour Record, and nineteen Monuments, including seven victories in Milan–San Remo. All this in twelve years of carrera, from 1965 to 1977. Eddy Merckx had a hunger for victory that bordered on the obsessive, earning him the nickname The Cannibal : he wanted to win everything and, if possible, crush his rivals, something he demonstrated from his very first participation in the Tour de France. In that 1969 edition, he took the yellow jersey with almost 18 minutes ahead of second place, Roger Pingeon, and won all the secondary classifications: the Mountains, the Points, the Combination, the team classification with Faema… and even the Combativity! Merckx swept the board in his first Tour thanks to his great mastery of all terrains, which translated into six stage wins: he won all three time trials, including the one on the last day in Paris, and prevailed on the summits of Ballon d’Alsace and Puy de Dôme, as well as beating Felice Gimondi in a head-to-head in the mountain stage between Briançon and Digne-les-Baines. He dominated everything: the time trials, plus the Alps and the Pyrenees. The following year, 1970, he increased his haul: he won the Tour with almost 13 minutes ahead of Zoetemelk and took eight stages, including the team time trial he won with Faema in Angers, three more individual time trials, and victories in the high mountains such as Mont Ventoux. Only the Points classification slipped away from him, which he lost by just five points to his Belgian compatriot, Walter Godefroot.

Merckx’s record in the Tour is phenomenal: he won one out of every five stages he raced in the French round (34 victories in 158 stages)

The overwhelming dominance of Eddy Merckx in the Tour de France could very well have come to an abrupt halt in 1971, when he found a formidable rival in the Spaniard Luis Ocaña, a cyclist with exceptional abilities in almost all terrains and a winning mentality comparable to the Belgian’s. That year, Ocaña positioned himself in the General Classification by winning at Puy de Dôme, and after Merckx lost the yellow jersey to Zoetemelk in the mountain stage at Grenoble, he launched a total offensive the next day on the way to Orcières-Merlette. The rider from Priego, Cuenca, attacked on the côte de Laffrey, 117 kilometers from the finish, and selected a breakaway from which he went solo on the climb to col de Noyer. Merckx, without team support, could not respond to one of the greatest exhibitions of all time. Ocaña won the stage and donned the yellow jersey, with almost ten minutes over the Belgian, who suffered his biggest defeat, saying: “Ocaña has killed us like El Cordobés kills his bulls ”. However, fate struck the rider from Priego, Cuenca, barely four days later, when he fell during the Pyrenean storm on the descent of the Col de Menté and was then run over by Zoetemelk as he tried to get up. Ocaña was evacuated to a hospital and his withdrawal left the way clear for Merckx's third victory in the Tour de France. Afterwards, the Belgian claimed his fourth victory in Paris in 1972, winning six stages and finishing almost 11 minutes ahead of Felice Gimondi, and dedicated 1973 to achieving the Vuelta a España – Giro d'Italia double, before returning in 1974 to win his fifth Tour. He did so by winning eight stages, including the one in Paris. Everything seemed set for Merckx to surpass Jacques Anquetil's five victories in 1975, but the five-time champion was attacked by a fanatic while leading on the Puy de Dôme stage, and two days later he paid the price, surrendering the yellow jersey to Bernard Thévenet during his historic collapse on the climb to Pra Loup. Merckx managed to finish second in Paris, less than three minutes behind the Frenchman, but he never won the Tour again. His seventh and final participation ended with a sixth place in 1977, more than 12 minutes behind Thévenet. He hung up his bike in 1978 with an incredible record in France: five-time Tour champion with 34 victories in 158 stages contested, including prologues. He won one out of every five stages he raced!

👉 If you also want to feel like a true cycling champion, visit our catalog of Elite Bicycles for Demanding Cyclists

Bernard Hinault

Bernard Hinault picked up the baton from Merckx at the end of the seventies as the great dominator of the Tour de France, rounding out the record that comes closest to the Belgian's: five overall wins in Paris, 28 stage victories, and 75 days wearing the yellow jersey. Like Merckx, Hinault won the Tour in his first appearance, in 1978, after delivering a masterstroke in the 72-kilometer time trial in Nancy, two days before reaching Paris. The Breton gained more than four minutes on the Dutchman Joop Zoetemelk to take the lead from him, and began to show his power in individual competition, the key to his victories, along with his extraordinary ambition. His dominance was already overwhelming in 1979, when he won his second Tour de France by taking seven stages and finishing more than 13 minutes ahead of the runner-up, once again Joop Zoetemelk. Hinault cemented his victory by winning against the clock on three key days: the uphill time trial to Superbagnères, and the time trials in Brussels and Morzine Avoriaz. His state of grace in individual competition led him to win that same year the Grand Prix des Nations, the unofficial world championship of the specialty. That victorious sequence in the Tour stopped in 1980, when the cold and rain that marked that edition had serious consequences for his knee. Hinault, who had already staked his claim with three stage wins, was forced to abandon in Pau due to tendonitis. The following year he made amends and won his third Tour with more than 14 minutes over Lucien Van Impe, after exerting overwhelming dominance in all terrains, especially in his specialty: he won the prologue in Nice and the time trials in Pau, Mulhouse, and Saint Priest, as well as striking a major blow in the Alps with a solo exhibition to win in La Pleynet. His fourth victory in the 1982 Tour followed that script: he staked his claim by winning the prologue in Basel, gave up the yellow for a few days, and retook the lead to keep it from stage 11, a 57-kilometer time trial. That day he lost by 18 seconds to Gerrie Knetemann, but the partial defeat to the Dutchman did not prevent Hinault from taking substantial differences from his rivals. The Breton would end up sealing the Tour by winning the next two time trials, in Martigues and Saint Priest, and sufficiently controlling his rivals' attacks in the Alps. The icing on the cake came in the Paris sprint, winning the last stage dressed in yellow and against a specialist like Adrie Van der Poel. Known as The Badger in France and as The Caiman in Spain, Bernard Hinault was at his peak and seemed headed for his fifth Tour in 1983, but his knees again took their toll shortly after his historic recital in the Ávila mountains stage, where he sealed his second victory in the Vuelta a España with a memorable ascent of the Puerto de Serranillos. He had to undergo surgery, this time on his right knee, and his absence paved the way for the emergence of young Laurent Fignon, Hinault's teammate on Cyrille Guimard's Renault team. Fignon ended up winning the 1983 Tour de France at just 22 years old, and Bernard Hinault left Renault in the winter, accepting a super lucrative offer from businessman Bernard Tapie to lead a new team: La Vie Claire.

Hinault achieved a total of seven podium finishes in the Tour de France and bid farewell to the French race in 1986 with a second place

In that context, the 1984 Tour de France was presented as a great duel between the two Frenchmen, considering that Hinault seemed recovered with his second place in the Giro d'Italia. The Breton seemed to confirm it by winning the prologue with a three-second advantage over Fignon, but it didn't go further than that. The Renault team, led by the blond Parisian with the ponytail, struck the first blow in the team time trial in Valenciennes, and Fignon personally took care of soundly beating Hinault in the individual time trial in Le Mans, as he also did in the next one, finishing in La Ruchère. Fignon ended up delivering a masterclass in the Alps, distancing Hinault in Alpe d’Huez and winning in La Plagne, to win the Tour by more than ten minutes over the Breton. Hinault saved second place by just over a minute ahead of a young and talented teammate in La Vie Claire: Greg LeMond. Stuck at four Tours, approaching 31 years old, and with the new generation breathing down his neck, Hinault faced the challenge of winning his fifth in 1985, relieved by the absence of Fignon, who was injured in the knee, but with LeMond challenging his leadership in the team. Then a pact emerged: LeMond would help Hinault win his fifth, and the following year they would switch roles so that the American could claim his first victory. The Badger He began the 1985 Tour by landing two major blows in the General Classification, first by emphatically winning the Strasbourg time trial, putting almost three minutes into LeMond, and second in the mountain stage at Morzine, where he took another minute and a half after finishing second behind a sensational Lucho Herrera, the best climber of the era. But it wasn't all a bed of roses: the fatigue accumulated after winning the Giro d'Italia and the strength of LeMond made Hinault suffer in the Pyrenean finales at Luz Ardiden and the Aubisque, in addition to yielding to the American in the final time trial at Lac Vassivière. Hinault won his fifth Tour by a narrow margin, by less than two minutes, but managed to enter the Olympus of five-time champions. Apparently satisfied to equal Anquetil and Merckx, Hinault declared that in 1986 he would honor the pact and help LeMond win his first Tour, but when the time came, he burst into the carrera with his most ambitious version, unable to resist the temptation to be the first cyclist to win six times in Paris. The unleashed Breton won the Nantes time trial and ended up donning the yellow jersey in the first Pyrenean stage, after a memorable breakaway with Perico Delgado. The Segovian was alert to read Hinault's move, who attacked in a special sprint more than ninety kilometers out with his teammate Jean François Bernard, and let himself be pulled along in his slipstream to the foot of the Col de la Marie Blanque. There, Bernard finished the job and Delgado and Hinault worked together until Pau, where the Frenchman yielded the stage victory to the Segovian and dressed in yellow, gaining more than four and a half minutes over LeMond. Hinault faced the next mountain stage with more than five minutes over LeMond, but he wasn't satisfied: he attacked again more than a hundred kilometers from the finish, seeking a definitive display, but faded on the ascent to Peyresourde and ended up being overtaken by LeMond on the final climb to Superbagnères. The American ended up putting more than four minutes into him, and although Hinault managed to save the yellow jersey, he could no longer withstand his young protégé in the Alps. LeMond took the lead in the grueling finish at the Col de Granon and the next day, at Alpe d’Huez, the two rivals and teammates left for history the image of the passing of the torch, crossing the finish line hand in hand. The old champion bade farewell to the Tour with second place, his seventh podium on the Champs-Élysées. At the end of 1986, he said goodbye to cycling for good by racing a cyclocross event in his hometown in Brittany, Yffiniac. The Badger returned to his den after marking a glorious era.

Jaques Anquetil

Jacques Anquetil was the first five-time champion in the history of the Tour de France and the great dominator of the carrera between the fifties and sixties, thanks to his exceptional abilities as a time trialist. Born in 1934 in the Norman town of Mont-Saint-Aignan, Anquetil left his job as a turner at the age of 18 to dedicate himself to cycling. He soon demonstrated his qualities, earning a bronze medal for France at the Helsinki Games, and winning the Grand Prix des Nations—the world's most prestigious time trial—at just 19 years old, a race he would go on to win nine times, the event's all-time record. That day he beat the great French champion of the era, Louison Bobet, in a 140-kilometer individual battle. His great dominance of the specialty was the key to his victories in the Tour de France, starting from his first participation in 1957, at the age of 23. In that edition, without major contenders like Bobet or Géminiani, and with fewer mountains than usual, Anquetil crushed the General Classification with a fifteen-minute advantage over the second-placed rider, the Belgian Marcel Janssens. He donned the yellow jersey on the Galibier stage, finishing in Briançon, and sealed the Tour in his specialty, winning the time trials of Montjuich, and especially that of Libourne, where he put more than three minutes into all his rivals. By then Anquetil already had the nickname Monsieur Crono, which would distinguish him throughout his carrera. Unlike other champions, that first victory in 1957 did not mark the start of a victorious sequence for Anquetil. Internal disagreements in the French teams, among stars like Louison Bobet, Raphael Géminiani, or Henri Anglade, combined with the brilliance of two legendary climbers like Charly Gaul and Federico Martín Bahamontes, kept Anquetil away from the top spot in Paris for three consecutive editions: in 1958, the year of Charly Gaul's great victory, the Norman collapsed on the Col de Porte, lost 23 minutes, and abandoned the next day suffering from pneumonia; in 1959, Anquetil could only manage third, in the face of the climbing exhibitions of Gaul and Bahamontes, and with time trial performances below his level, especially the day when The Eagle of Toledo seized the lead by dominating the Puy de Dôme mountain time trial. Anquetil finished more than five minutes behind Bahamontes, and had to wait two more years for the Paris podium, since in 1960 he chose to try to win the Giro d'Italia.

Anquetil experienced a fierce rivalry with his compatriot Raymond Poulidor and with Federico Martín Bahamontes, who forced him to give his all in his fourth and fifth Tour

Anquetil's victorious streak arrived with his four consecutive wins between 1961 and 1964, the period of his great duels with his compatriot Raymond Poulidor, another of the French legends. Still without that competition, Monsieur Crono He lived up to his nickname in 1961, dominating in the more than one hundred kilometers of time trial in that edition. Already in the second stage he began by donning the yellow jersey in the Versailles time trial, and he never let go of the lead. He put the finishing touch by crushing the competition in the 74.5-kilometer Périgueux time trial, in which he finished almost three minutes ahead of the second-placed rider, Charly Gaul. Anquetil won his second Tour with a 12-minute advantage over his closest rival, the Italian Guido Cardesi. The Norman champion faced much more opposition in the 1962 edition, which saw the debut of Raymond Poulidor and the emergence of Belgian Joseph Planckaert as a time trial specialist in the Tour. Anquetil won the first time trial in La Rochelle, but was beaten by Planckaert in the uphill time trial to Superbagnères, on a brilliant day for Bahamontes, who won the stage. The Belgian specialist dethroned the British Tom Simpson from the lead and defended it successfully in the mountains, while Poulidor began to show his quality by authoritatively winning the queen stage in Aix-les-Bains, a great Pyrenean crossing that included the climbs of Lautaret, Luitel, Porte, Cucheron, and Granier. With his rivals closing in, Anquetil eased the pressure with an indisputable victory in the 68-kilometer Lyon time trial, where he put more than five minutes into both Planckaert and Poulidor to deliver the decisive blow. He won in Paris with a 4:59 minute advantage over the Belgian, and 10:24 over his compatriot. With three Tours de France and a Giro d'Italia won, Anquetil presented himself as a global star in the 1963 edition. But that year he would face the colossal opposition of Bahamontes, who at 35 years old put the Norman champion under constant threat. Anquetil reached the mountains with barely any margin over the Spaniard, who showed a great performance on the flat, in the Angers time trial, and even on the cobblestones of Belgium. Only Bahamontes' lack of skill in the Pyrenean descents prevented the man from Toledo from distancing Anquetil, who managed to reach the Alps with about a three-minute lead. Bahamontes, who hadn't said his last word, made up the deficit with two consecutive exhibitions, the first to win the Grenoble stage, and the second to take the lead in Val-d’Isère after a memorable duel with Anquetil on the climbs of the Iseran and Croix de Fer. The next day, Anquetil had to contain the Spaniard on the Grand Saint Bernard, on the punishing Forclaz, and on the Col de Montet. Bahamontes, too impetuous, launched his attack early and escaped on the first climb, Anquetil neutralized him on the descent, and at the foot of the Forclaz came the controversy: Gémianini, Anquetil's director at Saint Raphael, faked a mechanical failure on the three-time champion’s bike—only in this way did the organization allow bike changes—and managed to get authorization to give him a lighter one, with a 46x26 gear combination, more suited to the upcoming 17% gradients. The trick gave Anquetil the boost to contain Bahamontes, who threw everything at him on the climb, in a succession of ever-stronger attacks that the Frenchman resisted as best he could. At the summit he conceded only a few seconds to the man from Toledo, whom he then finished off in the Chamonix sprint, taking advantage of the slipstream of a motorcycle. He would seal his fourth Tour by authoritatively winning the Besançon time trial.

Perhaps the fact that he was the first rider to win five Tours de France lessened his ambition to go for a sixth and he looked for new challenges.

Anquetil's fifth victory in 1964 was the tightest of all, thanks on one hand to the emergence of the best Raymond Poulidor, and on the other to a new, very competitive version of Bahamontes, who was already 36 years old. Both rivals achieved three important victories in the mountains; Poulidor in Bagnères de Luchon, and Bahamontes in Briançon and Pau. Anquetil was able to distance the Spaniard when he took the yellow jersey in the Bayonne time trial, but not his compatriot, who showed his great form by finishing second less than a minute behind. With the Tour in his grasp, the carrera reached the Puy de Dôme, where a memorable duel between the two Frenchmen took place. Poulidor, 56 seconds behind Anquetil, needed to gain a substantial advantage over the leader to have a margin for the final time trial in Paris. The challenger tried everything, battling side by side, but could only pull away in the final stretch and Anquetil was able to limit the damage: he saved the yellow by 14 seconds, more than enough to seal his fifth Tour with another time trial victory in Paris, but not enough to win the favor of the French public, who were rooting for Poulidor. The 55 seconds that separated them in the General Classification is the smallest margin in the five victories of the Norman champion. Anquetil never returned to the Tour de France, thus leaving the carrera without being defeated by it, unlike the five-time champions who would come after. Perhaps being the first rider in history to reach five wins diminished his ambition to go for a sixth, but those were different times and there were other challenges with which he could win over the French fans, a battle he had clearly lost to Poulidor. The Norman was only able to recover some of that sympathy in 1965 and outside the Tour, when he diverted his energies to achieving an unprecedented feat: he beat Poulidor again in the Dauphiné Libéré, a kind of Tour reduced to ten stages, and barely nine hours after finishing the Dauphiné, he went to race the Bordeaux–Paris, a 557-kilometer classic whose start was at two in the morning. With hardly any sleep, Anquetil started badly, had stomach problems and nearly abandoned, but everything changed when his director, Raphael Géminiani, touched his pride by saying: “I was wrong about you.” The Norman responded by catching up to Tom Simpson and Jean Stablinsky, and then left them behind entering Paris, to win the carrera in 15 hours and three minutes. The Parc des Princes gave him an ovation he had never heard while wearing yellow.

Miguel Induráin

Miguel Induráin remains the only one among the five-time Tour de France champions to have achieved his five victories consecutively, after the organization decided to erase Lance Armstrong's seven consecutive wins from the record books due to doping. Born in the Navarrese town of Villava, into a family of farmers, few would have bet that the strapping youngster who joined the Villavés Cycling Club at the age of 11 would not only become the best Spanish cyclist of all time, but also one of the great legends of the Tour de France. He was too big to keep up with the climbers in the high mountains, and much of his extraordinary power was lost in countering his high weight, which was simply that of a young man approaching six foot three. It was his director at Villavés, Pepe Barruso, who contacted the Reynolds team after Induráin burst onto the youth scene with five victories in 1981, his first year in the category, confirming the quality he had shown since childhood. In his second year, already under the watchful eye of José Miguel Echávarri, Induráin increased that tally to eleven wins and ended up making the leap to the amateur Reynolds team, backed by exceptional abilities as a classics rider and sprinter that made him aim high on the national scene. Nineteen more victories as an amateur were the springboard that launched Induráin to the professional Reynolds team in September 1984. The Navarrese team decided to have Induráin debut in the 1985 Tour de France, after the young cyclist wore the yellow jersey in the Vuelta a España for four days, until he lost it in his theoretically forbidden terrain of the mountains, climbing to the Lakes of Covadonga. It was not a good debut in France: Induráin abandoned that Tour in the fourth stage due to illness, and the same happened in 1986, when he arrived at the Grande Boucle after winning the Tour de l'Avenir, showing his power in the fight against the clock. However, that year he left a first mark on the Tour de France, finishing third in the sprint for the seventh stage, behind Ludo Peeters and Ron Kiefel. 1986 was a key year in Induráin's development. Reynolds decided to explore his real possibilities as a potential grand tour winner and subjected the rider to various medical tests, which revealed that the Navarrese had extraordinary, almost unlimited, potential. Based on that data, Induráin began to focus his preparation on countering his deficit in the mountains by losing some weight and carrying out specific training sessions. The results soon arrived. After finishing his first Tour de France in 1987 far down the General Classification, the Navarrese became an important piece in the Reynolds team that helped Perico Delgado win in Paris in 1988, and capped his season with a top-level victory in the Volta a Catalunya. Induráin ended up resolving most of the doubts about his climbing skills the following year, when he won Paris–Nice climbing with the best, and when he achieved his first stage victory in the Tour de France, winning at the Cauterets summit after launching an attack descending the Col de la Marie Blanque, following Reynolds' strategy to wear down LeMond and Fignon in favor of Perico Delgado. In that same edition, Induráin outperformed his Segovian leader and his two main rivals in the time trial climb to Orcières-Merlette, in what was third, only surpassed by Steven Rooks and Marino Lejarreta.

Induráin won his first Tour by holding on in the mountains and sealing the win in the time trial. In the next four Tours, he perfected the script even more: superlative against the clock, relentless in the mountains.

The feelings about Induráin's great evolution were finally confirmed in the 1990 Tour de France, where he finished tenth overall despite being Perico Delgado's luxury domestique. The Navarrese rider outperformed all the big favorites in the 61-kilometer time trial in Epinal, where he finished second behind Mexican Raúl Alcalá, and ended up third in the Villard de Lans stage. In case there were any doubts, in the mountains he confirmed his impressive progress with a second place in Millau, behind Marino Lejarreta, and with an impressive victory in Luz Ardiden, where he dropped leader Greg LeMond with his pace in the final kilometer to win solo. Induráin's great performance sparked a more than reasonable debate about the team leadership at Reynolds, after Perico Delgado was left off the podium and, above all, after calculating that the twelve-minute loss by the Navarrese in the overall standings compared to the winner, Greg LeMond, was due to his work as a coequipier in favor of the Segovian. The Reynolds team took note of this in 1991 and decided that Induráin should share leadership with Delgado. The Navarrese began to dispel doubts by winning the 73-kilometer time trial in Alençon, where he beat LeMond by eight seconds and distanced Delgado by more than two minutes. The American wore yellow that day until, in the first Pyrenean stage, he and the rest of the favorites allowed a breakaway that lifted the Frenchman Luc Leblanc into the lead. That new situation took a historic turn the next day, in the memorable queen stage between Jaca and Val Louron, 232 kilometers with climbs to the Portalet, Aubisque, Tourmalet, and Aspin, before the final ascent, all under suffocating heat in the Pyrenees. The key moment occurs on the colossal Tourmalet, where LeMond decides to attack ten kilometers from the summit, in a show of false strength that is quickly exposed when the Italian Claudio Chiappucci increases the pace and from the group of favorites, Delgado, the leader Leblanc, Fignon, and LeMond himself fall behind. Induráin, climbing unflinchingly at his own pace, goes on the attack as soon as he crests and breaks away on the first descent of the Tourmalet to ride alone toward Sainte Marie de Campan. In the valley, he waits for Chiappucci and the pair agree to share the work, which blows up the Tour: the Italian will set the pace on the climbs to Aspin and Val Louron, and Induráin will take strong turns in the valleys. Chiappucci will win the stage, after more than seven hours of carrera, and the Navarrese will wear yellow for the first time, gaining substantial differences: Gianni Bugno at 1:29 minutes; Fignon at 2:50; LeMond at 7:18… Delgado arrives even further behind and, when asked at the finish if he is happy, shows his bewilderment. He does not know about his teammate’s feat. Induráin will finish off his first Tour by resisting Gianni Bugno’s attacks in the mountains and sealing victory with another win in the Maçon time trial, on the eve of the arrival in Paris. It is the beginning of a legendary streak. The Navarrese will win the next four Tours, perfecting the script even further: superlative against the clock, relentless in the mountains. In 1992, he wins the prologue in San Sebastián and begins to seal the Tour in Luxembourg, where he delivers what many consider the best time trial of all time. He wins with a three-minute advantage over the second, his teammate Armand de las Cuevas, distances Bugno and LeMond by around four minutes, and overtakes Laurent Fignon, who had started six minutes earlier. Already in yellow, Induráin consolidates his lead in another stage for the history books, the one in Sestrières, where Chiappucci wins solo after attacking more than 200 kilometers from the finish and the Navarrese, third at the finish, gains another minute over Bugno. The final blow comes two days before Paris, when Induráin wins the Blois time trial and rounds off his second triumph